Our Research

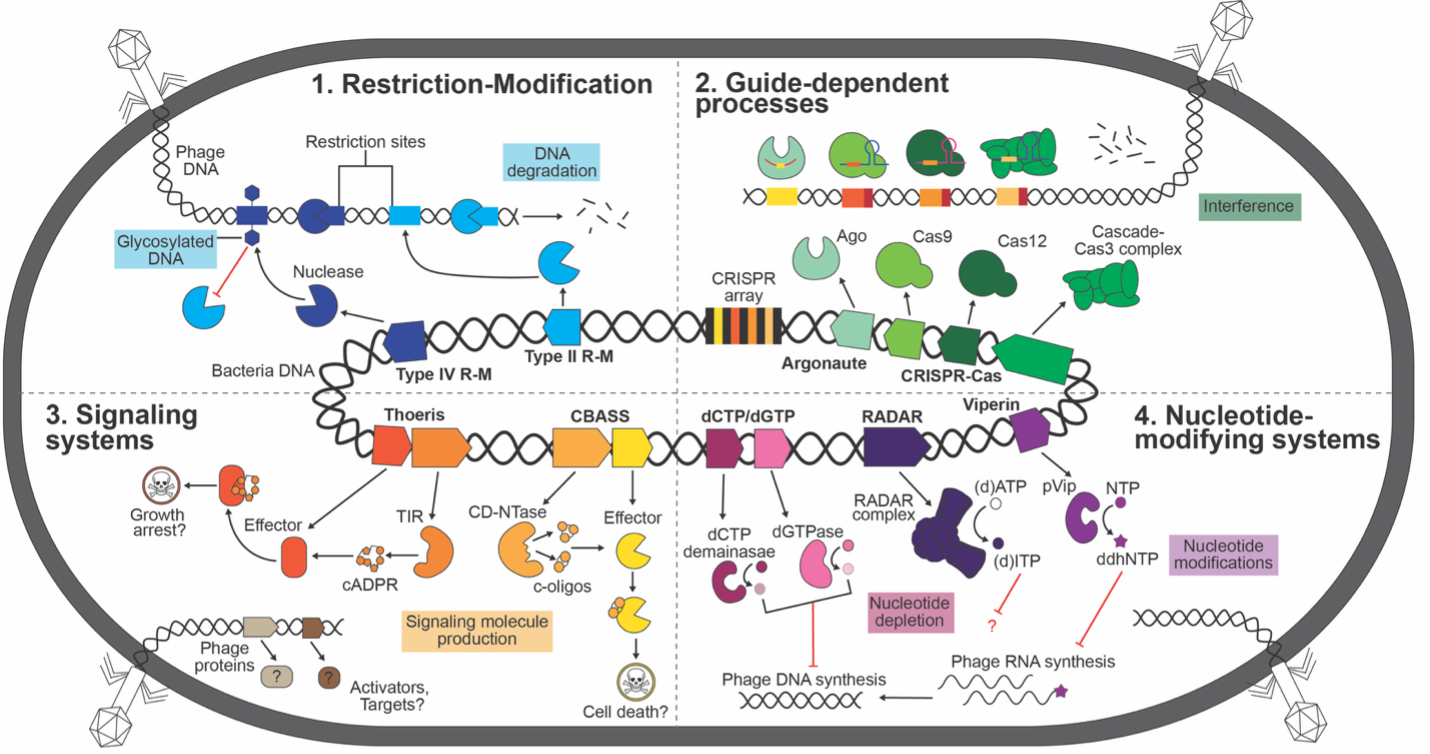

In the Bondy-Denomy Lab, we delve into the intricate molecular battles between bacteria and their viral predators, bacteriophages (phages). Our research focuses on bacterial anti-phage systems—such as CRISPR-Cas, restriction-modification systems, CBASS, Thoeris—and the sophisticated countermeasures phages employ to evade these defenses. Through a combination of genetic, molecular, cell biological, and biochemical approaches, we aim to unravel the complexities of these interactions, shedding light on microbial ecosystems and paving the way for innovative applications in biotechnology and medicine.

The group focuses phage-host interaction experiments on model organisms with tractable genetics that are also prominent human pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli.

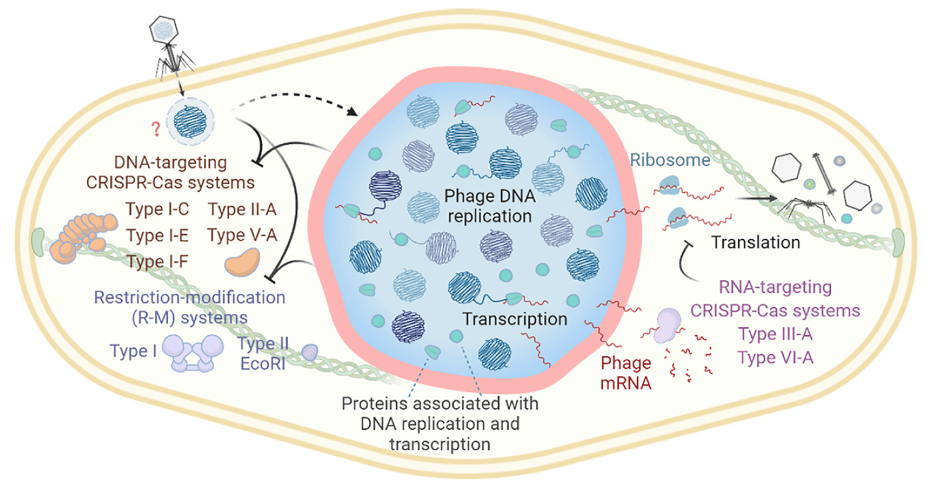

Phage Nucleus and Jumbo Phages

We investigate the unique strategies of jumbo phages, particularly their formation of endosome-like lipid vesicles and nucleus-like compartments that shield viral DNA from host defenses. Our studies have elucidated biochemical and functional aspects of these compartments, highlighting their role in phage replication and immune evasion.

Discovery of Novel Defense Systems

Utilizing bioinformatics and experimental approaches, we uncover previously unrecognized bacterial defense mechanisms and their corresponding phage counter-defenses. We primarily focus on endogenously functional defenses, in the hopes of understanding the true limitations to phage host range. This work expands our understanding of the evolutionary arms race between bacteria and phages and identifies potential new targets for antimicrobial strategies.

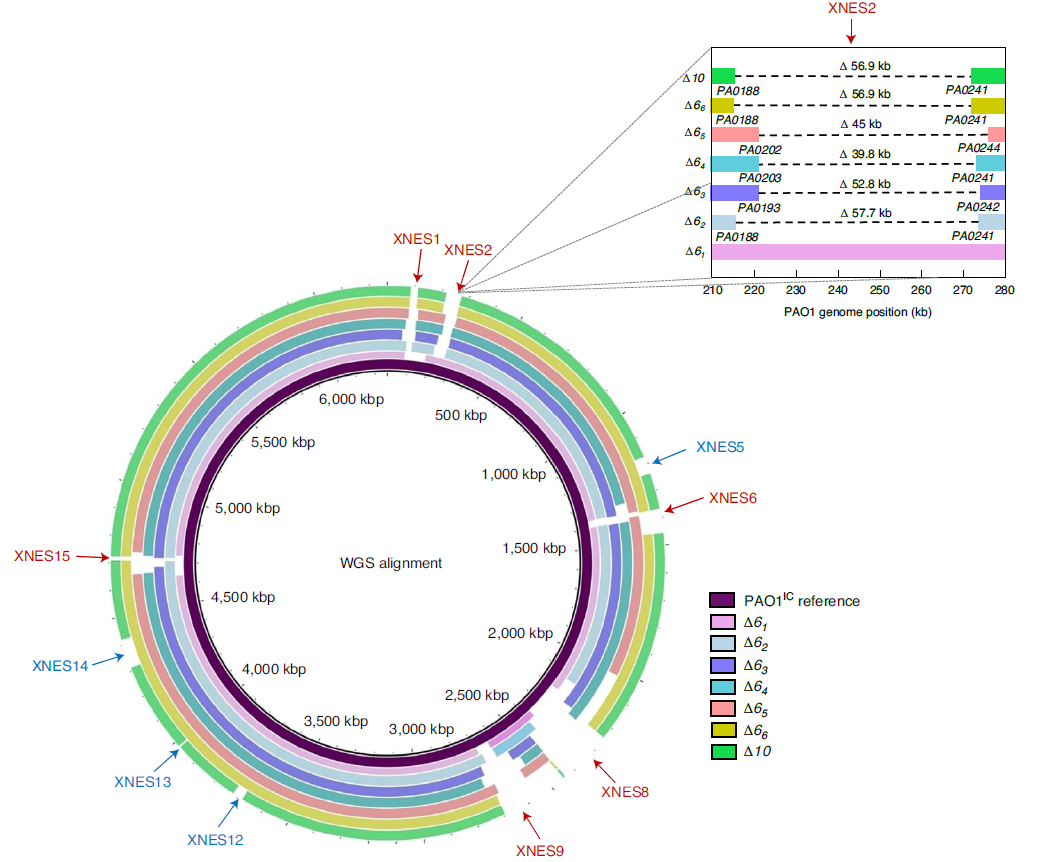

Anti-CBASS and Anti-Thoeris Proteins

CRISPR-Cas systems were functionally characterized just 13 years ago as bacterial immune systems that target bacteriophages. Since then, there has been an explosion of interest in this system for its widespread presence in the microbial world as well as its facile programmability. This has formed the basis of a revolutionary and Nobel prize winning gene editing technique, CRISPR-Cas9. However, Cas3 enzymes are natural effectors for Type I CRISPR-Cas system that harness the benefit of programmability, with the upside or large genomic deletions. We have harnessed the Type I CRISPR-Cas3 effector for making large deletions in bacterial genomes, with specified (via homology directed repair) or unspecific boundaries. We are using this technology to support other discovery efforts in the lab and working on new applications for Cas3. We are also applying this enzyme and others to phage engineering efforts, in the hopes of making it possible to enable genetic tractability for any phage.

Phage Engineering with Cas13

We are developing novel phage engineering approaches using Cas13 to modify phage genomes in biased and unbiased manners. This technology enables us to study phage gene function at scale and engineer therapeutic phages with tailored properties for translational applications.

Activation of bacterial defense by non-essential phage proteins

Multiple studies in recent years have revealed that common “double bind” that phages experience where inhibitors of one defense system activates another. This explains why all phages don’t simply have all inhibitors. We are interested in how inhibitors limit host range and the molecular mechanisms that explain this phenomenon.

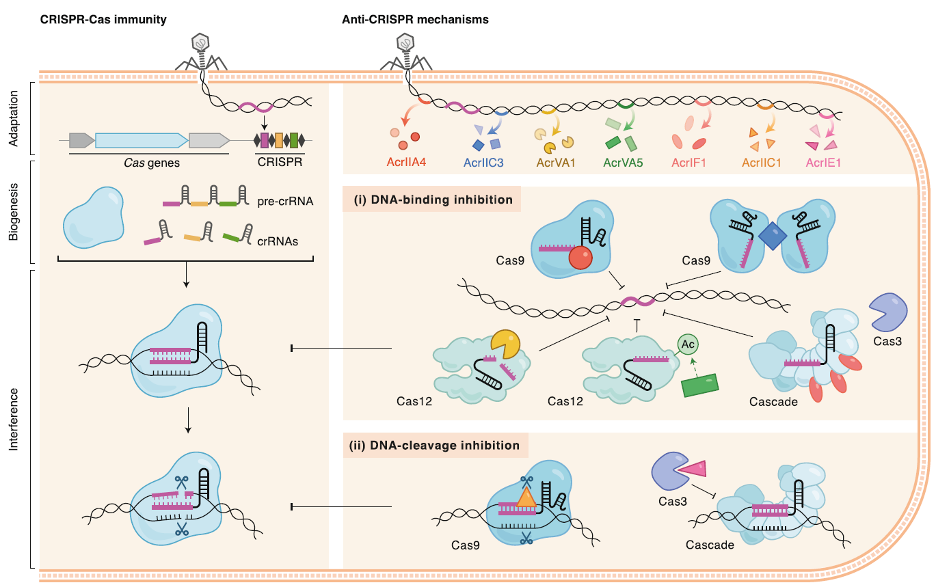

Anti-CRISPR Proteins

Building upon our discovery of the first anti-CRISPR proteins, we continue to identify and characterize these phage-encoded inhibitors. Our recent work has expanded the mechanistic possibilities for anti-CRISPRs including enzymatic modifications, Cas protein and cas mRNA degradation. Understanding these interactions provides insights into phage biology and offers tools for regulating CRISPR-based technologies.